- Home

- Amanda Palmer

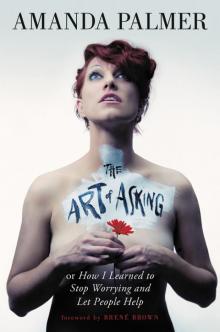

The Art of Asking Page 2

The Art of Asking Read online

Page 2

And on the second floor of the house, while Neil slept beside me, I was having a full-blown panic attack.

Somewhere down there I suppose I was freaking out about getting married, full stop. It was feeling very real all of sudden, with all the family around. What was I doing? Who was this guy?

But mostly, I was freaking out about money.

My Kickstarter was about to launch and I was pretty confident it would bring in plenty of cash—I’d crunched the numbers—but I wasn’t on tour, I was in northern Scotland, throwing a wedding party and putting a new band together, earning nothing. I’d just had a talk with my accountant, who had informed me that I wasn’t going to have enough money to cover my office staff, band, road crew, and regular monthly expenses unless I dropped everything and went back on the road immediately—or unless I took out a loan to bridge the gap for a few months before the Kickstarter and new touring checks arrived.

This wasn’t an unfamiliar situation. To the recurring dismay of my managers, I’d already spent most of my adult life putting all of my business profits straight back into the next recording or art project once I had recovered my costs. In the course of my rocking-and-rolling career, I’d been rich, poor, and in-between…and never paid much attention to the running tally as long as I wasn’t flat broke, which occasionally happened due to an unforeseen tax bill or the unexpected tanking of a touring show. And that was never the end of the world: I’d borrow money to get through a tight spot from friends or family and promptly pay it back when the next check came in.

I was an expert at riding that line and asking for help when I needed it, and, far from feeling ashamed of it, I prided myself on my spotless interpersonal credit history. I also took comfort in the fact that a lot of my musician friends (and business friends, for that matter) went through similar cycles of feast and famine. In short, it always worked out.

Only this time, there was a different problem. The problem was that Neil wanted to loan me the money.

And I wouldn’t take the help.

We were married.

And I still couldn’t take it.

Everybody thought I was weird not to take it.

But I still couldn’t take it.

I’d been earning my own salary as a working musician for over a decade, had my own dedicated employees and office, paid my own bills, could get out of any bind on my own, and had always been financially independent from any person I was sleeping with. Not only that, I was celebrated for being an unshaven feminist icon, a DIY queen, the one who loudly left her label and started her own business. The idea of people seeing me taking help from my husband was…cringe-y. But I dealt, using humor. Neil would usually pick up the tab at nice restaurants, and we’d simply make light of it.

Totally fine with me, I’d joke. You’re richer.

Then I’d make sure to pay for breakfast and the cab fare to the airport the next morning. It gave me a deep sense of comfort knowing that even if we shared some expenses here and there, I didn’t need his money.

I knew the current gap I had to cover was a small one, I knew I was about to release my giant new crowdfunded record, I knew I was due to go back on tour, and everything logically dictated that this nice guy—to whom I was married—could loan me the money. And it was no big deal.

But I just. Couldn’t. Do. It.

I’d chatted about this with Alina and Josh over coffee a few weeks before the wedding party. They were true intimates I’d gone to high school with, at whose own wedding I’d been the best man (our mutual friend Eugene had been the maid of honor) and we’d been sharing our personal dramas for years, usually while I was crashing on ever-nicer couches in their apartments as they moved from Hoboken to Brooklyn to Manhattan. We were taking turns bouncing their newborn baby, Zoe, on our laps, I had just told them that I didn’t want to use any of Neil’s money to cover my upcoming cash shortage, and they were looking at me like I was an idiot.

But that’s so weird, Alina said. She’s a songwriter and a published author. My situation wasn’t foreign to her. You guys are married.

So what? I squirmed. I just don’t feel comfortable doing it. I don’t know. Maybe I’m too afraid that my friends will judge me.

But, Amanda…we’re you’re friends, Alina pointed out, and we think you’re crazy.

Josh, the tenured philosophy professor, nodded in agreement, then looked at me with his typically furrowed brow.

How long do you think you’ll keep it this way? Forever? Like, you’ll be married for fifty years but you’ll just never mix your incomes?

I didn’t have an answer for that.

Neil wasn’t the type to attach strings, or play games, but it was my deepest fear that I’d be somehow beholden, indebted to him.

This was a new feeling, this panic, or rather, an old one: I hadn’t felt this freaked out since I was a teenager battling constant existential crises. But now my head was a vortex of questions: How could I possibly take money from Neil? What would people think? Would he hold it over my head? Maybe I should just put this album off another year and tour? What would I do with the band I just hired? What about my staff? How would they deal? Why can’t I just handle this gracefully? Why am I freaking out?

I left the bed after an entire night of tossing and fretting. I went into the bathroom and turned on the light.

What is WRONG with you? I asked the puffy-eyed, snot-leaking, deranged person that was staring back at me from the mirror.

I dunno, she answered. But this is not good. I was scaring myself. What was happening to me? Was I crazy?

It was six a.m., the sun was just beginning to rise, and the sheep were baa-ing mournfully. We had to be awake at eight to drive to the wedding party.

I went back to bed and crawled into Neil’s armpit. He was out cold, and snoring. I looked at him. I loved this man so much. We’d been together for over two years and I’d learned to trust him completely—trust him not to hurt me, not to judge me. But something still felt stuck shut, like a door that should open but just doesn’t budge. I tossed my body to the other side of the bed and tried to sleep, but the cyclone of thoughts didn’t stop. You have to take his help. You can’t take his help. You have to take his help. And then I started to bawl, feeling completely out of control and foolish. I was tired of crying alone, I guess, and ready to talk.

Darling, what’s wrong?

He’s British. He calls me darling.

I…I’m freaking out.

I can see that. Is it the money thing? He put his arms around me.

I don’t know what I’m going to do for these next few months, I snorfled. I think I should put off making the record if I can’t afford to pay everyone right now. I’ll just tour for the next year and forget about the Kickstarter until…I don’t know, I can probably borrow the money from someone else to get through the next few months…maybe I can…

Why someone else? he interrupted quietly. Amanda…we’re married.

So what?

So just get over it and borrow the money from me. Or TAKE the money from me. Why else did we get married? You’d do the same thing for me if I were in an in-between spot. Wouldn’t you?

Of course I would.

So, what is HAPPENING? I’d much rather you let me cover you for a few months than see you in this state, it’s getting disturbing. All you have to do is ASK me. I married you. I love you. I want to HELP. You won’t let me help you.

I’m sorry. This is so weird—I’ve dealt with this shit so many times and it’s never bothered me like this. It’s crazy. I feel crazy. Neil, am I crazy?

You’re not crazy, darling.

He held me. I did feel crazy. I couldn’t rid myself of this one pounding, irritating thought, reverberating through my head like a bitter riddle, an impossible logic puzzle that I just couldn’t shake off or solve.

I was an adult, for Christ’s sake.

Who’d taken money from random people, on the street, for years.

Who openly preached the gospe

l of crowdfunding, community, help, asking, and random, delightful generosity.

Who could ask any stranger in the world—with a loud, brave laugh—for a tampon.

Why couldn’t I ask my own husband for help?

We ask each other, daily, for little things: A quarter for the parking meter. An empty chair in a café. A lighter. A lift across town. And we must all, at one point or another, ask for the more difficult things: A promotion. An introduction to a friend. An introduction to a book. A loan. An STD test. A kidney.

If I learned anything from the surprising resonance of my TED talk, it was this:

Everybody struggles with asking.

From what I’ve seen, it isn’t so much the act of asking that paralyzes us—it’s what lies beneath: the fear of being vulnerable, the fear of rejection, the fear of looking needy or weak. The fear of being seen as a burdensome member of the community instead of a productive one.

It points, fundamentally, to our separation from one another.

American culture in particular has instilled in us the bizarre notion that to ask for help amounts to an admission of failure. But some of the most powerful, successful, admired people in the world seem, to me, to have something in common: they ask constantly, creatively, compassionately, and gracefully.

And to be sure: when you ask, there’s always the possibility of a no on the other side of the request. If we don’t allow for that no, we’re not actually asking, we’re either begging or demanding. But it is the fear of the no that keeps so many of our mouths sewn tightly shut.

Often it is our own sense that we are undeserving of help that has immobilized us. Whether it’s in the arts, at work, or in our relationships, we often resist asking not only because we’re afraid of rejection but also because we don’t even think we deserve what we’re asking for. We have to truly believe in the validity of what we’re asking for—which can be incredibly hard work and requires a tightrope walk above the doom-valley of arrogance and entitlement. And even after finding that balance, how we ask, and how we receive the answer—allowing, even embracing, the no—is just as important as finding that feeling of valid-ness.

When you examine the genesis of great works of art, successful start-ups, and revolutionary shifts in politics, you can always trace back a history of monetary and nonmonetary exchange, the hidden patrons and underlying favors. We may love the modern myth of Steve Jobs slaving away in his parents’ garage to create the first Apple computer, but the biopic doesn’t tackle the potentially awkward scene in which—probably over a macrobiotic meatloaf dinner—Steve had to ask his parents for the garage. All we know is that his parents said yes. And now we have iPhones. Every artist and entrepreneur I know has a story of a mentor, teacher, or unsung patron who loaned them money, space, or some kind of strange, ass-saving resource. Whatever it took.

I don’t think I’ve perfected the art of asking, not by a long shot, but I can see now that I’ve been an unknowing apprentice of the art for ages—and what a long, strange trip it’s been.

It started in earnest the day I painted myself white, put on a wedding gown, took a deep breath, and, clutching a fistful of flowers, climbed up onto a milk crate in the middle of Harvard Square.

You may have a memory of when you first, as a child, started connecting the dots of the world. Perhaps outside on a cold-spring-day school field trip, mud on your shoes, mentally straying from the given tasks at hand, as you began to find patterns and connections where you didn’t notice them before. You may remember being excited by your discoveries, and maybe you held them up proudly to the other kids, saying:

did you ever notice that this looks like this?

the shapes on this leaf look like the cracks in this puddle of ice

which look like the veins on the back of my hand

which look like the hairs stuck to the back of her sweater…

Collecting the dots. Then connecting them. And then sharing the connections with those around you. This is how a creative human works. Collecting, connecting, sharing.

All artists work in different mediums, but they also differ when it comes to those three departments. Some artists love the act of collecting. We might call this experiencing, or emotionally and intellectually processing the world around us: the ingredients—the puddles of ice, the sweater—that go into the poetic metaphor. Or the wider and longer-term collection: the time it takes to fall in and out of love, so that you can describe it in song, or the time it takes a painter to gaze at a landscape before deciding to capture it on canvas. Or the nearly three years Thoreau needed to live simply on the side of a pond, watching sunrises and sunsets through the seasons, before he could give Walden to the world.

Some artists devote more time to connecting the dots they’ve already collected: think of a sculptor who hammers away for a year on a single statue, a novelist who works five years to perfect a story, or a musician who spends a decade composing a single symphony—connecting the dots to attain the perfect piece of art. Thoreau himself needed another three years after his time in the cabin to distill and connect his experiences into the most beautiful and direct writing possible.

Like most stage performers, I’ve always been most passionate about the final phase: the sharing. There are lots of ways to share. Writers share when someone else reads or listens to their words in a book, a blog, a tweet. Painters share by hanging their work, or by sliding the sketchbook to a friend across the coffee-shop table. Stage performers also collect and connect (in the form of experiencing, writing, creating, and rehearsing), but there is a different kind of joy in that moment of human-to-human transmission: from you to the eyes and ears of an audience, whether fireside at a party or on a stage in front of thousands. I’m a sharing addict. But no matter the scale or setting, one truth remains: the act of sharing, especially when you’re starting out, is fucking difficult.

There’s always a moment of extreme bravery involved in this question:

…will you look?

It starts when you’re little. Back in the field: the veins of the leaf looked like your hand, and you said it, out loud, to the kids walking next to you.

You may have seen the lights go on in their eyes, as you shared your discovery—Whoa, you’re right! Cool—and felt the first joys of sharing with an audience. Or you may have been laughed at by your friends and scolded by the teacher, who explained, patiently:

Today isn’t “looking for patterns” day.

This is not the time for that.

This is the time to get back in line, to fill in your worksheet, to answer the correct questions.

But your urge was to connect the dots and share, because that, not the worksheet, is what interested you.

This impulse to connect the dots—and to share what you’ve connected—is the urge that makes you an artist. If you’re using words or symbols to connect the dots, whether you’re a “professional artist” or not, you are an artistic force in the world.

When artists work well, they connect people to themselves, and they stitch people to one another, through this shared experience of discovering a connection that wasn’t visible before.

Have you ever noticed that this looks like this?

And with the same delight that we took as children in seeing a face in a cloud, grown-up artists draw the lines between the bigger dots of grown-up life: sex, love, vanity, violence, illness, death.

Art pries us open. A violent character in a film reflects us like a dark mirror; the shades of a painting cause us to look up into the sky, seeing new colors; we finally weep for a dead friend when we hear that long-lost song we both loved come unexpectedly over the radio waves.

I never feel more inspired than when watching another artist explode their passionate craft into the world—most of my best songs were written in the wake of seeing other artists bleed their hearts onto the page or the stage.

Artists connect the dots—we don’t need to interpret the lines between them. We just draw them and then present our

connections to the world as a gift, to be taken or left. This IS the artistic act, and it’s done every day by many people who don’t even think to call themselves artists.

Then again, some people are crazy enough to think they can make a living at it.

THE PERFECT FIT

I could make a dress

A robe fit for a prince

I could clothe a continent

But I can’t sew a stitch

I can paint my face

And stand very very still

It’s not very practical

But it still pays the bills

I can’t change my name

But I could be your type

I can dance and win at games

Like backgammon and Life

I used to be the smart one

Sharp as a tack

Funny how that skipping years ahead

Has held me back

I used to be the bright one

Top in my class

Funny what they give you when you

Just learn how to ask

I can write a song

But I can’t sing in key

I can play piano

But I never learned to read

I can’t trap a mouse

But I can pet a cat

No, I’m really serious!

I’m really very good at that

I can’t fix a car

But I can fix a flat

I could fix a lot of things

But I’d rather not get into that

I used to be the bright one

Smart as a whip

Funny how you slip so far when

Teachers don’t keep track of it

The Art of Asking

The Art of Asking