- Home

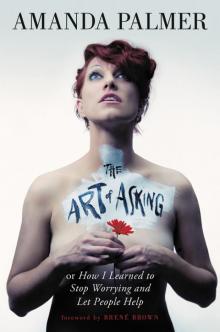

- Amanda Palmer

The Art of Asking

The Art of Asking Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Newsletters

Copyright Page

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO MY MUTTI,

who, through her love, first taught me how to ask

Foreword

by Brené Brown

A decade or so ago in Boston, Amanda performed on the street as a human statue—a white-faced, eight-foot-tall bride statue to be exact. From a distance, you could have watched a passerby stop to put money in the hat in front of her crate and then smile as Amanda looked that person lovingly in the eye and handed over a flower from her bouquet. I would’ve been harder to spot. I would have been the person finding the widest path possible to avoid the human statue. It’s not that I don’t throw my share of dollars into the busking hats—I do. It’s just that I like to stay at a safe distance, then, as inconspicuously as possible, put my money in and make a beeline for anonymity. I would have gone to great lengths to avoid making eye contact with a statue. I didn’t want a flower; I wanted to be unnoticed.

From a distance, Amanda Palmer and I have nothing in common. While she’s crowdsurfing in Berlin wearing nothing but her red ukulele and combat boots, or plotting to overthrow the music industry, I’m likely driving a carpool, collecting data, or, if it’s Sunday, maybe even sitting in church.

But this book is not about seeing people from safe distances—that seductive place where most of us live, hide, and run to for what we think is emotional safety. The Art of Asking is a book about cultivating trust and getting as close as possible to love, vulnerability, and connection. Uncomfortably close. Dangerously close. Beautifully close. And uncomfortably close is exactly where we need to be if we want to transform this culture of scarcity and fundamental distrust.

Distance is a liar. It distorts the way we see ourselves and the way we understand each other. Very few writers can awaken us to that reality like Amanda. Her life and her career have been a study in intimacy and connection. Her lab is her love affair with her art, her community, and the people with whom she shares her life.

I spent most of my life trying to create a safe distance between me and anything that felt uncertain and anyone who could possibly hurt me. But like Amanda, I have learned that the best way to find light in the darkness is not by pushing people away but by falling straight into them.

As it turns out, Amanda and I aren’t different at all. Not when you look close up—which is ultimately the only looking that matters when it comes to connection.

Family, research, church—these are the places I show up to with wild abandon and feel connected in my life. These are the places I turn to in order to crowdsource what I need: love, connection, and faith. And now, because of Amanda, when I’m weary or scared or need something from my communities, I ask. I’m not great at it, but I do it. And you know what I love more than anything about Amanda? Her honesty. She’s not always great at asking either. She struggles like the rest of us. And it’s in her stories of struggling to show up and be vulnerable that I most clearly see myself, my fight, and our shared humanity.

This book is a gift being offered to us by an uninhibited artist, a courageous innovator, a hardscrabble shitstarter—a woman who has the finely tuned and hard-fought ability to see into the parts of our humanity that need to be seen the most. Take the flower.

WHO’S GOT A TAMPON? I JUST GOT MY PERIOD, I will announce loudly to nobody in particular in a women’s bathroom in a San Francisco restaurant, or to a co-ed dressing room of a music festival in Prague, or to the unsuspecting gatherers in a kitchen at a party in Sydney, Munich, or Cincinnati.

Invariably, across the world, I have seen and heard the rustling of female hands through backpacks and purses, until the triumphant moment when a stranger fishes one out with a kind smile. No money is ever exchanged. The unspoken universal understanding is:

Today, it is my turn to take the tampon.

Tomorrow, it shall be yours.

There is a constant, karmic tampon circle. It also exists, I’ve found, with Kleenex, cigarettes, and ballpoint pens.

I’ve often wondered: are there women who are just TOO embarrassed to ask? Women who would rather just roll up a huge wad of toilet paper into their underwear rather than dare to ask a room full of strangers for a favor? There must be. But not me. Hell no. I am totally not afraid to ask. For anything.

I am SHAMELESS.

I think.

I’m thirty-eight. I started my first band, The Dresden Dolls, when I was twenty-five, and didn’t put out my first major-label record until I was twenty-eight, which is, in the eyes of the traditional music industry, a geriatric age at which to debut.

For the past thirteen years or so, I’ve toured constantly, rarely sleeping in the same place for more than a few nights, playing music for people nonstop, in almost every situation imaginable. Clubs, bars, theaters, sports arenas, festivals, from CBGB in New York to the Sydney Opera House. I’ve played entire evenings with my own hometown’s world-renowned orchestra at Boston Symphony Hall. I’ve met and sometimes toured with my idols—Cyndi Lauper, Trent Reznor from Nine Inch Nails, David Bowie, “Weird Al” Yankovic, Peter from Peter, Paul and Mary. I’ve written, played, and sung hundreds of songs in recording studios all over the world.

I’m glad I started on the late side. It gave me time to have a real life, and a long span of years in which I had to creatively figure out how to pay my rent every month. I spent my late teens and my twenties juggling dozens of jobs, but I mostly worked as a living statue: a street performer standing in the middle of the sidewalk dressed as a white-faced bride. (You’ve seen us statue folk, yes? You’ve probably wondered who we are in Real Life. Greetings. We’re Real.)

Being a statue was a job in which I embodied the pure, physical manifestation of asking: I spent five years perched motionless on a milk crate with a hat at my feet, waiting for passersby to drop in a dollar in exchange for a moment of human connection.

But I also explored other enlightening forms of employment in my early twenties: I was an ice cream and coffee barista working for $9.50 an hour (plus tips); an unlicensed massage therapist working out of my college dorm room (no happy endings, $35 per hour); a naming and branding consultant for dot-com companies ($2,000 per list of domain-cleared names); a playwright and director (usually unpaid: in fact, I usually lost my own money, buying props); a waitress in a German beer garden (about 75 deutsche marks a night, with tips); a vendor of clothes recycled from thrift shops and resold to my college campus center (I could make $50 a day); an assistant in a picture-framing shop ($14 per hour); an actress in experimental films (paid in joy, wine, and pizza); a nude drawing/painting model for art schools ($12 to $18 per hour); an organizer and hostess of donation-only underground salons (paid enough money to cover the liquor and event space); a clothes-check girl for illegal sex-fetish loft parties ($100 per party), and, through that job, a sewing assistant for a bespoke leather-handcuff manufacturer ($20 per hour); a stripper (about $50 per hour, but it really depended on the night); and—briefly—a dominatrix ($350 per hour—but there were, obviously, very necessary clothing and accessory expenses).

Every single one of these jobs taught me about human vulnerability.

Mostly, I learned a lot about asking.

Almost every important human encounter boil

s down to the act, and the art, of asking.

Asking is, in itself, the fundamental building block of any relationship. Constantly and usually indirectly, often wordlessly, we ask each other—our bosses, our spouses, our friends, our employees—in order to build and maintain our relationships with one another.

Will you help me?

Can I trust you?

Are you going to screw me over?

Are you suuuure I can trust you?

And so often, underneath it all, these questions originate in our basic, human longing to know:

Do you love me?

In 2012, I was invited to give a talk at the TED conference, which was daunting; I’m not a professional speaker. Having battled my way—very publicly—out of my major-label recording contract a few years earlier, I had decided that I’d look to my fans to make my next album through Kickstarter, a crowdfunding platform that had recently opened up the doors for thousands of other creators to finance their work with the direct backing of their supporters. My Kickstarter backers had spent a collective $1.2 million to preorder and pay for my latest full-band album, Theatre Is Evil, making it the biggest music project in crowdfunding history.

Crowdfunding, for the uninitiated, is a way to raise money for ventures (creative, tech, personal, and otherwise) by asking individuals (the Crowd) to contribute to one large online pool of capital (the Funding). Sites like Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and GoFundMe have cropped up all over the world to ease the transaction between those asking for help and those answering that call, and to make that transaction as practical as possible.

Like any new transactional tool, though, it’s gotten complicated. It’s become an online Wild West as artists and creators of all stripes try to navigate the weird new waters of exchanging money for art. The very existence of crowdfunding has presented us all with a deeper set of underlying questions:

How do we ask each other for help?

When can we ask?

Who’s allowed to ask?

My Kickstarter was dramatically successful: my backers—almost twenty-five thousand of them—had been following my personal story for years. They were thrilled to be able to aid and abet my independence from a label. However, besides the breathless calls from reporters who’d never heard of me (not surprising since I’d never had an inch of ink in Rolling Stone) asking about why all these people helped me, I was surprised by some of the negative reactions to its success. As I launched my campaign, I walked right into a wider cultural debate that was already raging about whether crowdfunding should be allowed at all; some critics were dismissing it out of hand as a crass form of “digital panhandling.”

Apparently, it was distasteful to ask. I was targeted as the worst offender for a lot of reasons: because I’d already been promoted by a major label, because I had a famous husband, because I was a flaming narcissist.

Things went from dark to darker in the months after my Kickstarter as I set off to tour the world with my band and put out my usual call to local volunteer musicians who might want to join us onstage for a few songs. We were a tight community, and I’d been doing things like that for years. I was lambasted in the press.

My crowdfunding success, plus the attention it drew, led TED to invite me, a relatively unknown indie rock musician, to talk for twelve minutes on a stage usually reserved for top scientists, inventors, and educators. Trying to figure out exactly what to say and how to say it was—to put it mildly—scary as shit.

I considered writing a twelve-minute performance-art opera, featuring ukulele and piano, dramatizing my entire life from The Womb to The Kickstarter. Fortunately, I decided against that and opted for a straightforward explanation of my experience as a street performer, my crowdfunding success and the ensuing backlash, and how I saw an undeniable connection between the two.

As I was writing it, I aimed my TED talk at a narrow slice of my social circle: my awkward, embarrassed musician friends. Crowdfunding was getting many of them excited but anxious. I’d been helping a lot of friends out with their own Kickstarter campaigns, and chatting with them about their experiences at local bars, at parties, in backstage dressing rooms before shows. I wanted to address a fundamental topic that had been troubling me: To tell my artist friends that it was okay to ask. It was okay to ask for money, and it was okay to ask for help.

Lots of my friends had already successfully used crowdfunding to make new works possible: albums, film projects, newfangled instruments, art-party barges made of recycled garbage—things that never would have existed without this new way of sharing and exchanging energy. But many of them were also struggling with it. I’d been watching.

Each online crowdfunding pitch features a video in which the creator explains their mission and delivers their appeal. I found myself cringing at the parade of crowdfunding videos in which my friends looked (or avoided looking) into the camera, stammering, Okay, heh heh, it’s AWKWARD TIME! Hi, everybody, um, here we go. Oh my god. We are so, so sorry to be asking, this is so embarrassing, but…please help us fund our album, because…

I wanted to tell my friends it was not only unnecessary to act shame-ridden and apologetic, it was counterproductive.

I wanted to tell them that in truth, many people enthusiastically loved helping artists. That this wasn’t a one-sided game. That working artists and their supportive audiences are two necessary parts in a complex ecosystem. That shame pollutes an environment of asking and giving that thrives on trust and openness. I was hoping I could give them some sort of cosmic, universal permission to stop over-apologizing, stop fretting, stop justifying, and for god’s sake…just ASK.

I prepared for more than a month, pacing in the basement of a rented house and running my TED talk script past dozens of friends and family members, trying to condense everything I had to say into twelve minutes. Then I flew to Long Beach, California, took a deep breath, delivered the talk, and received a standing ovation. A few minutes after I got off the stage, a woman came up to me in the lobby of the conference center and introduced herself.

I was still in a daze. The talk had taken so much brain space to deliver, and I finally had my head back to myself.

I’m the speaker coach here, she began.

I froze. My talk was supposed to have been exactly twelve minutes. I’d paused a few times, and lost my place, and I’d gone well over thirteen. Oh shit, I thought. TED is going to fire me. I mean, they couldn’t really fire me. The deed was done. But still. I shook her hand.

Hi! I’m really, really sorry I went so over the time limit. Really sorry. I got totally thrown. Was it okay, though? Did I TED well? Am I fired?

No, silly, you’re not fired. Not at all. Your talk… And she couldn’t go on. Her eyes welled up.

I stood there, baffled. Why was the TED speaker coach looking as if she was going to cry at me?

Your talk made me realize something I’ve been battling with for years. I’m also an artist, a playwright. I have so many people willing to help me, and all I have to do is…but I can’t…I haven’t been able to…

Ask?

Exactly. To ask. So simple. Your talk unlocked something really profound for me. Why the hell do we find it so hard to ask, especially if others are so willing to give? So, thank you. Thank you so much. Such a gift you gave.

I gave her a hug.

And she was just the first.

Two days later, the talk was posted to the TED site and YouTube. Within a day it had 100,000 views. Then a million. Then, a year later, eight million. It wasn’t the view counts that astounded me: it was the stories that came with them, whether in online comments or from people who would stop me in the street and ask to share a moment, not because they knew my music, but because they recognized me from seeing the talk online.

The nurses, the newspaper editors, the chemical engineers, the yoga teachers, and the truck drivers who felt like I’d been speaking straight to them. The architects and the nonprofit coordinators and the freelance photographers who told me that they�

��d “always had a hard time asking.” A lot of them held me, hugged me, thanked me, cried.

My talk had resonated way beyond its intended audience of sheepish indie rockers who found it impossible to ask for five bucks on Kickstarter without putting a bag over their heads.

I held everybody’s hands, listened to their stories. The small-business owners, solar-panel designers, school librarians, wedding planners, foreign-aid workers…

One thing was clear: these people weren’t scared musicians. They were just…a bunch of people.

I’d apparently hit a nerve. But WHAT nerve, exactly?

I didn’t have a truly good answer for that until I thought back to Neil’s house, to the night before our wedding party.

A few years before this all happened, I met Neil Gaiman.

Neil’s famous, for a writer. He’s famous for an anyone.

For years, Neil and I had chased each other around the globe in the cracks of our schedules, me on the Endless Road of Rock and Roll, him on the parallel road of Touring Writer, falling in love diagonally and at varying speed, before finally eloping in our friends’ living room because we couldn’t handle the stress of a giant wedding.

We didn’t want to disrespect our families, though, so we promised them that we would throw a big, official family wedding party a few months later. We decided to do it in the UK, where the bulk of them live. (Neil is British, and so are a lot of my cousins.) Furthermore, the setting was magic: Neil owned a house on a teeny island in Scotland, which was coincidentally the birthplace of my maternal grandmother. It is a windswept, breathtaking-but-desolate grassy rock from which my ancestors fled in poverty-stricken terror in the early 1900s, seeking a brighter, less-breathtaking-but-less-desolate future overseas in the promising neighborhoods of the Bronx.

The night before the wedding party, Neil and I bedded down early to get a full night’s sleep, anticipating an epic day of party organizing, eating, drinking, and nervously introducing two hundred family members to one another. Neil’s three grown-up kids were staying in the house with us, along with Neil’s mother and an assortment of Gaiman relatives. They were all snuggled away in their beds across the hall, up the stairs, a few stray young cousins roughing it in tents on the back lawn.

The Art of Asking

The Art of Asking